In the early 1970s, the full-page martial arts instruction ads of Count Dante captured the imagination of a generation of comic book readers. But then, just two years after the mysterious death of Bruce Lee in 1973, this controversial fighter would also turn up dead under equally mysterious circumstances.

(from pacotaylor.medium.com)

It was in the early 1960s, way back in the day, that the popularity of Asia’s martial arts began an infectious spread across America’s then still divided racial and cultural landscape. In Los Angeles in 1961, Master Ark Wong of the Wah Que Studio became one of the first teachers of the martial arts to break the long observed “kung-fu color line,” which barred the teaching of China’s sacred fighting arts to anyone not of Chinese ancestry. Around that same time, Wong’s bold action was being mirrored by an unknown martial artist named Bruce Lee, who had started teaching kung fu to non-Chinese pupils at his Oakland, California studio.

But interest in martial arts was on the rise nationwide, and it was at this same time that the soon-to-be infamous martial artist known as Count Dante began teaching the karate techniques of Japan to the young roughnecks of Chicago.

-Black Belt-

A former US Marine and Ranger, Count Dante (born John Keehan) began the study and practice of the martial arts in the mid to late 1950s, training under Robert Trias, a former colonel in the US Army C.I.D. Reserves. Trias, who was credited with opening America’s very first karate school in 1946, was author of Hand is My Sword (1956), recognized as the first martial arts book published in the US.

Though trained primarily under Trias, Dante claimed to have also trained for a time at Bruce Lee’s studio around 1961 or 1962. A 7th dan black belt in karate, Dante was said to have been proficient not only in the Japanese, Chinese, and Okinawan open-hand fighting styles but also in judo, aikido, and still other fighting systems.

Count Dante was also an undefeated champion of numerous national kumite or freestyle fighting competitions, the only exception being a disqualification from the North American Championships, held at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

As early as 1964, while serving as the head instructor of Trias’ US Karate Association (USKA), Dante was lauded as being one of the top karate instructors in the United States by America’s premiere martial arts publication Black Belt. But he soon abandoned his position at the Trias organization under a heavy cloud of speculation. The fighter would later allege in an interview with Black Belt that the split with USKA was prompted by Trias’ “prejudicial bias” against his African-American students.

“It’s no secret that I have a great many blacks in my school,” the fighter reported. “That was the reason behind my rift with Robert Trias and the USKA. At that time, the USKA didn’t have any blacks in the organization, except mine, and Trias didn’t like that one bit. He even told me that I had promoted the second black in his organization. And, according to him, the first was by mistake. He told me that if he had known this fellow he had named a black belt in the Philippines was black he wouldn’t have done it. He told me that he slipped…the USKA did not award black belts to blacks.”

Acrimoniously separated from Trias, Dante would move on to become one of the principal organizers of what was then The World Karate Championships, and to also found the Imperial Academy of Fighting Arts and the Midwest Karate Yudanshakai.

In August of 1967, the popular fighter also promoted what was to be this nation’s first “full contact” martial arts tournament. And by competition’s end, he himself would be declared “Worlds Deadliest Fighting Master” by the World Federation of Fighting Arts Committee, for his (allegedly) having bested some of the world’s foremost martial arts masters in the no-holds- barred judo, boxing, wrestling, kung-fu, karate and aikido “death matches.”

But then, shockingly, Dante retired from the ring in 1968 and refused to take on any challenger for the coveted title that he soon widely publicize.

During his career, Dante authored a number of articles published by the martial arts magazines of the day, and three booklets, among them the widely advertised World’s Deadliest Fighting Secrets (1968), for which he was best known. Ads for the slim publication were seen by many in the pages of Marvel comics in the mid-1970s, where Dante was billed as the “Supreme Grand Master of the Black Dragon Fighting Society” and the “Deadliest Man Alive.”

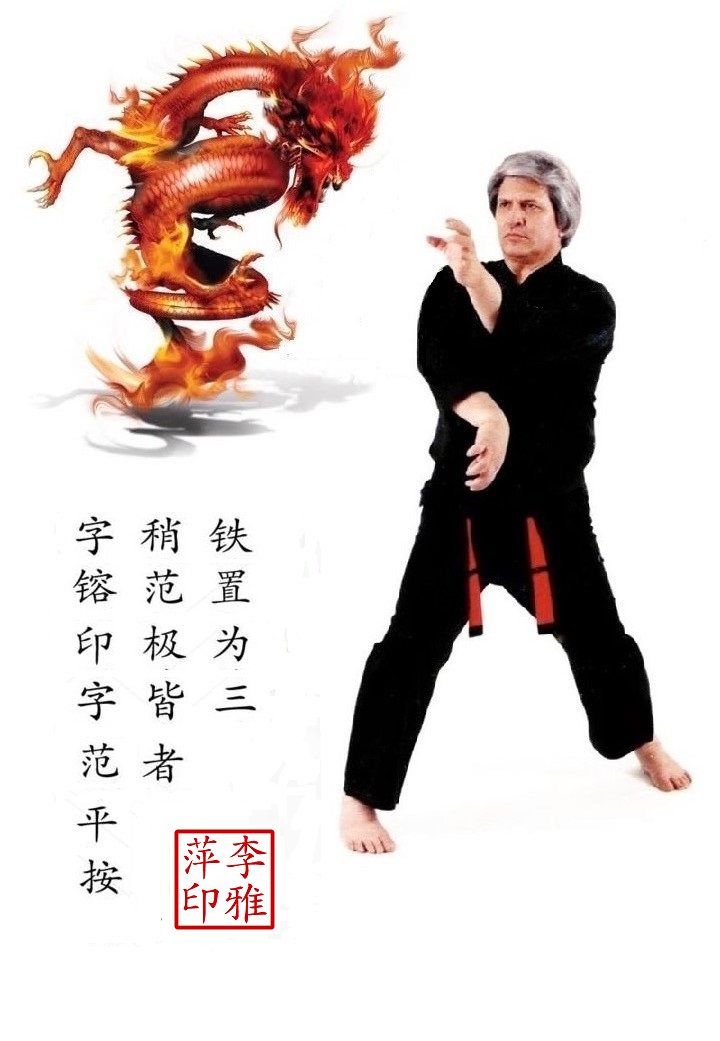

On that pulse-pounding ad page, Dante loomed as a badass karate master. Garbed in a black martial arts gi, the fighter’s chiseled arms slithered menacingly from dark nothingness. His fighting stance was punctuated with fierce, fang-like fingers coiled tightly into the dreaded dim mak (death touch). Empty eyes bled down from sharply arched eyebrows, and a black beard, edged sideburns and a pointed widow’s peak ascended into the rounded crown of a faux Afro.

In early photographs that accompanied articles in martial arts magazines like Black Belt, Dante appeared with a much lighter and clean-cut visage than the dramatic image presented in ads for the Worlds Deadliest Fighting Secrets. Surprisingly handsome for a fighter, Dante’s face exuded a boyish, even innocent quality. But under that visage lurked a violent mind that proved Dante to be much more like a wolf in a sheep’s clothing than the guitless boy next door.

-Deadly Hands of Count Dante-

According to writer Massad Ayoob, Dante held an “obscene fascination” with the most brutal aspects of martial arts. From that interest came the fighting system he developed in the late 1960s called Kata Dante (“Dance of the Deadly Hands” or “Dance of Death”). The system, which Ayoob described as teaching more of a fighting attitude than an actual fighting technique, was designed for street combat, and advocated explosive attacks, or counter attacks that oozed with ruthlessness and brutality.

Eager to prove the effectiveness of his fighting system, Dante issued challenges to a number of well-known fighters of the day. On July 28th, 1968, word of one such challenge made the headlines of the gossip rag The National Informer. Bravely — or insanely — Dante showed up at the South Side Chicago home of Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay) to challenge the World Heavyweight Boxing Champion to an unanswered duel.

Dante’s macho posturing and aggressive taunts lead to several heated verbal altercations between his and various other martial arts schools in Chicago. They quickly escalated into the windows of a number of area institutions being broken out, and then students — as well as some of their instructors — being jumped and beaten.

In July of 1965, Dante and associate Douglas Dwyer, an instructor at the Tai-Jutso School of Judo, were arrested in a failed attempt to dynamite rival school, Judo and Karate Center. Detectives spotted the men while they were in the process of taping a 40-inch dynamite fuse and blasting cap to a window at the school. While running in the dark to evade capture, Dante and Dwyer sprinted blindly into a dead end alley and were soon apprehended.

Explaining the incident to news sources, Dante described the attempted bombing as a “drunken prank,” and claimed that neither he nor Dwyer had any intention of hurting anyone at the school. Dwyer said that he and his would-be partner-in-crime had been drinking at a party before the early morning caper and that the act was a “crazy and stupid stunt.”

Convicted of attempted arson, Count Dante was sentenced to two years probation. But a short time after the man’s probation ended, he was once again involved in another stupid stunt, one that would take a very tragic turn.

On the night of April 22nd, 1970, Dante was embroiled in another of Chicago’s infamous “dojo wars” with Black Cobra Hall of Kung Fu Kempo. The battle was instigated by Dante himself and several of his disciples from the House of Dante.

According to students at the Black Cobra Hall, six unknown assailants entered the school with their leader, who flashed a deputy sheriff’s badge and claimed that the students of the school were all being placed under arrest. Dante then then quickly struck Black Cobra Hall instructor Jose Gonzales with an unseen weapon that nearly caused Gonzales to lose his right eye, and a violent free-for-all ensued.

Tipped-off by an anonymous source just minutes after the fight began, police officers arrived just in time to apprehend Dante and his fellow assailants as they were attempting to flee the scene. But officers would also find Dante’s close friend and student, James Koncevic, lying bloodied in a doorway, dead from a knife wound.

Jerome Greenwald, the Black Cobra Hall student charged with Koncevic’s death, told police that, while being pummeled by Koncevic, he grabbed a knife from the wall — one of several weapons on display — and jabbed the blade into his assailant’s abdomen. The Judge proceeding over Greenwald’s trial would rule the life-ending act to be one committed in self-defense.

Count Dante, identified as the man responsible for engineering the invasion, was charged with impersonating an officer, criminal damage to property, and aggravated battery. The incident would leave him branded as a dangerous shit starter for the rest of his career.

-Exit the Dragon-

On July 20th, 1973, both the martial arts and the entertainment worlds were rocked as reports emerged that kung fu superstar Bruce Lee had died in Hong Kong under a shroud of mysterious circumstance. Lee, suffering with an intense headache, had taken equagesic tablets (aspirin compound), a prescription painkiller given to him by Betty Ting Pei, the actress slated to costar with Lee in the unfinished film Game of Death. Lee lied down for a nap in Pei’s apartment, slipped into a coma and passed away in the night.

The coroner who conducted the autopsy ruled the Lee’s tragic demise as “death by misadventure,” and concluded that Lee had suffered severe cerebral edema, or brain swelling, in a strange reaction to one of the ingredients in the prescription painkiller.

Despite that ruling, throughout Lee’s adoring fan base , reeling from shock and unwilling to accept his tragic death as accidental ,a writhing hydra of speculation arose.

One popular rumor suggested that his death had been orchestrated by the Chinese crime organization known as the Triads in retribution for Bruce’s refusal to indulge them “protection fees.” Another suggested that Lee had been involved in a street challenge and was killed by an opponent’s use of dim mak, a mystical technique involving strategic blows to the body of an opponent, engineered to cause sickness, unconsciousness and eventually death.

On August 15th, 1973, nearly one month after his passing, Enter the Dragon, the film that Lee completed in April of that year, was released to US theaters. Boosted by the star’s even greater posthumous notoriety, the film earned a worldwide box-office take of more than $90 million and ignited rabid international interest in the martial arts.

Feverishly, film studios on both sides of the Pacific Ocean began searching for another martial artist who could fill the ravenous void left in Bruce Lee’s wake. Count Dante was said to have been tapped by Counselor Films to appear in a screen test, and flown to Hollywood for casting consideration.

According to Kata Dante disciple William Aguilar, however, Counselor’s attempts to capture his controversial mentor on film would prove “futile.” The man claimed that the cameras used by the studio somehow failed to capture Dante’s “brutal, lightning fast hand techniques.”

An additional claim is also made that the company’s insurance coverage was canceled after the Dante shoot — which actually seems to explains where the failure in the screen test occurred.

Apparently, the “World’s Deadliest Man” refused to pull any of his punches and kicks for the screen test, resulting in injuries to several of the martial artists hired by the studio for his shoot. And again, as it had so many times before, the brutality employed by Dante against others wound up working just as effectively against the man himself.

-Death Match-

Aside from his martial arts teaching, Dante also apparently dabbled in a curious assortment of career pursuits. He worked as the director of a wig and hairpiece firm, as a hair stylist and even as a beauty consultant. He also managed several car lots on Chicago’s South Side; one of two jobs that hinted a connection between Count Dante and the Chicago-based mafia.

By March of 1975, a year and a half after his almost brush with film stardom, Dante was hustling for bucks as an adult book dealer (another seeming mob connection), while also making guest appearances on the Massachusetts “Ku-Fu Death Match” tournament and exhibition circuit.

On March 16th, 1975, Dante made an appearance at the World Fighting Arts Expo held at the Roseland Ballroom in Taunton, MA. The appearance would be one of his last. On May 26th, 1975 — as with Bruce Lee before him — death came for Count Dante as he slept.

On his death certificate, coroners attributed his demise to natural causes: ulcerative colitis — bleeding ulcers, in laymen’s terms. Dante’s wife, however, would state publicly her doubts about that ruling, pointing out how in the autopsy report coroners wrote that her husband’s “whole insides” had been strangely eaten away as if by cancer. “But they didn’t put that down on the death certificate,” she claimed.

And despite the official coroner’s report, rumors suggesting other, more provocative alternatives that explained Dante’s demise were passed though the proverbial grapevine.

One that circulated around Chicago for years after his passing suggested that Dante had himself been on the receiving end of a deadly dose of dim mak, and dispatched in a late night duel at the hands of a now nameless sensei from a South Side dojo–one of the many area instructors he had challenged over the years.

Another suggested that Dante had died under an order issued by the mafia, and killed by way of a sub-dermal injection of “cancer cells,” similar to a claim that had been made by Jack Ruby, the mob connected killer of John F. Kennedy assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald. Now five decades later, the aura of mystery surrounding the death of Count Dante remains.

Whatever the actual means to his end, it was also speculated by some that Dante was fully aware that his time was near, in that he publicly pondered near the time of his passing how he would be remembered after he was gone.

In a statement made to Black Belt a short time before his death, the fighter reflected on how a great many in the martial arts world had resented and feared Bruce Lee while he was alive. According to Dante, they only honored Lee’s breathtaking legacy after he was gone, because it was only then that “they weren’t afraid of him anymore.”

And then, invoking the legend of the samurai Miyamoto Musashi, Dante declared, “Look up his history,” as if seeking validation for — or vindication from — his more than checkered past. “Musashi is the hero of Japan, yet he murdered innocent men, women and children for money. He was a stone killer. They despised him when he was alive and canonized him when he was dead.”

“Mark my words,” he said with a hint of warning. “That’s what they’ll do to me.”

Some five decades later, the jury may still be out on whether the controversial Count Dante will be up for canonization in any karate of fame. But the distinct vision of the martial arts that he once wove into the pop cultural fabric of this country is undisputed. More than fifty years after his mysterious death, that vision resonates still.

Under Count Dante’s instruction, an untold number of highly skilled martial artists have been trained in martial arts dojos throughout Chicago, and cities in Massachusetts. Today, many of those students, and even the students of those students, continue training highly skilled martial arts students of their own.

In an article published the fall of 1975 in Marvel’s hybrid comic book/martial arts mag Deadly Hands of Kung Fu, author Val Eads eulogized Count Dante saying:

“Although his talk about deadly and crippling techniques embarrassed and angered many martial artists, there are also many who defended his philosophy as being necessary in face of the realities of life. There are also many people who witnessed Dante live up to the image he made for himself. Although he was controversial, for every martial artist who remembers him as a crackpot there is another who remembers Count Dante as a gentleman and a fighter.”

And in the mind of this Generation X writer from Chicago, Count Dante, forever immortalized in the ads of old school comics and martial arts magazines as “The Deadliest Man Alive,” is fondly remembered that very same way: as a crackpot, as a gentleman, and as a fighter.

https://pacotaylor.medium.com/man-you-come-right-out-of-a-comic-book-the-unbelievable-life-death-of-count-dante-b41b5521bf99